- Home

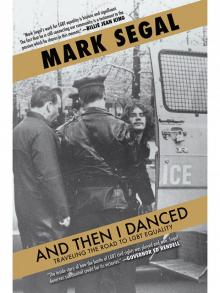

- Mark Segal

And Then I Danced

And Then I Danced Read online

Table of Contents

___________________

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Chapter 1: The Boy from the Projects

Chapter 2: Stonewall

Chapter 3: Mom, Don’t Worry, I’ll Be Arrested Today

Chapter 4: Walter

Chapter 5: After Cronkite

Chapter 6: Talking Sex with the Wall Street Journal

Chapter 7: Tits and Ass

Chapter 8: Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome

Chapter 9: Clout

Chapter 10: Adventures with a Publisher

Chapter 11: Bringing Up Baby

Chapter 12: Elton John and a Bag Full of Diamonds

Chapter 13: Meeting with Mr. President

Chapter 14: An Army of Pink Hard Hats

Chapter 15: And Then We Danced

Photographs

About Mark Segal

Copyright & Credits

About Akashic Books

To Jason Villemez, who each day tells me there is more I can do and encourages me to dream and follow that vision; my parents Marty and Shirley Segal, who encouraged their son to be who he was; and Fannie Weinstein, suffragette and civil rights supporter, who taught her grandson well.

Acknowledgments

As a newspaper publisher, my knowledge of book publishing was nonexistent. A project of this scale does not get done without those people who have the expertise and believe in it to the point that they encourage you to make yourself vulnerable. Marva Allen, my copublisher, is a legend in the African American literary community who was one of the first women to break that glass ceiling. Upon our first meeting she told me simply, “You have a story to share and we will get this done.” She soon introduced me to her colleagues Marie Brown and Regina Brooks at Open Lens, and to the folks at Akashic Books, which hosts their imprint. Again at first meeting they gave me the encouragement I needed since the endeavor frightened me. After all, up until this project, I only wrote a 500-word weekly column, not an entire book. Thanks too to my actress friend Sheryl Lee Ralph, who introduced me to my future publisher.

After the first draft, we invited the talented editor Michael Denneny (The Mayor of Castro Street: The Life and Times of Harvey Milk and The Band Played On) to work on the project. He took it on and explained to me that this was history that had to be recorded. He also took a book that was full of flashbacks and showed me how to put it in a mostly chronological order. I believe his special sense of history and enthusiasm for this book made me fully realize that it had to be completed.

I must thank my close friends and family, who were aware of the manuscript and kept it quiet knowing that I wanted to be able to abandon it at any time, and understood that they would read it only when it was published. Also, Richard Aregood, former Pulitzer Prize editorial writer for the Philadelphia Daily News, who helped me shape the early version of this book.

I have a new sense of appreciation for LGBT historians who assisted with getting me the hard facts needed to underscore issues in the book, especially Sean Strub, author of Body Counts and founder of POZ magazine, who read my chapter on AIDS to assure its accuracy.

Thanks to my family at PGN, who allowed me the time away from the office to do my various projects and who fill me with pride by delivering award-winning journalism each week.

Many writers forget the work our editors do, and my editors had a special task in teaching me to put my passion into words, and then into a weekly column. To Al Patrick, Pattie Tihey, Sarah Blazucki, and Jen Colletta—thank you.

Finally, thank you to those who lived this history with me and are still with us, and to those gone pioneers and friends who inspired and worked with me. To my sisters and brothers in Gay Liberation Front New York who were my teachers, especially Jerry Hoose, who in true GLF fashion debated with me many parts of this book. (Jerry lost his battle with cancer before it was completed but his spirit lives in these pages). To my Gay Youth New York family, who allowed me to learn to lead. To my friends in LGBT media, who fight each day to inform our community. And to my friends in mainstream media, who taught an activist how to become a publisher.

Introduction

The rights that the LGBT community have gained and continue to gain, from marriage equality to employment nondiscrimination, are the result of decades of hard work from individuals who in the early days, most of the time, lived off the kindness of friends. In the 1960s, being a gay activist was not a profession; it was an unpaid job for those dedicated to LGBT equality. When the newly energized gay movement sprouted from the Stonewall riots of June 1969, there was no organizational support with deep pockets, bailing people out of jail. Those of us in the riot didn’t have any best practices or contingency plans to fall back on. The only gay person I knew who was receiving a modest stipend was Reverend Troy Perry, who was building the gay-friendly Metropolitan Community Church.

Thanks to the early activists, today the LGBT community is represented in every segment of American society: from Fortune 500 CEOs, to leaders in education, labor, public safety, and politics, including at the White House. The Obama administration has appointed out LGBT individuals in almost every capacity at the highest levels of government.

We were able to get here because of the tireless work of pioneers such as Frank Kameny, Barbara Gittings, Harry Hay, Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon, Randy Wicker, Reverend Troy Perry, Martha Shelley, Marty Robinson, many of my brothers and sisters in New York’s Gay Liberation Front, and so many others, including a man named Henry Gerber, who in 1925 created the first LGBT organization in the nation in Chicago.

Since we had no funds, we had to be creative in our efforts to change individuals’ minds about who we were. This is my story but it is also an American story, one that illuminates and documents the historic LGBT struggle for equality. In most cases, I’ve kept to a chronological narrative, but sometimes, as is typical for me, I go off and explore issues that deserve further discussion and attention.

Chapter 1

The Boy from the Projects

I was an outsider from the beginning. When I was born in 1951 to Martin and Shirley Segal, my father was the proprietor of a store in South Philly, one of those neighborhood groceries that were once common throughout the big cities; in New York they are called bodegas. His proprietorship was short-lived. Against the backdrop of row homes and big Catholic churches, my father’s store was condemned by eminent domain to be replaced by a housing project. My parents, with two little boys and no work, were provided for by the city. At some point, we moved to nearby Wilson Park. There, as a member of the only Jewish family in a South Philadelphia housing project, I got an expert lesson in isolation. Kids who lived there said that we were from the other side of the tracks, and it was a reality since the housing project was sandwiched in on one side by an expressway and on the other by the 25th Street railroad bridge. We were, literally, across the street and an underpass away from a middle-class, mostly Catholic neighborhood.

We were poor, which in the Jewish community is almost a sin against God, or in our case a sin against the rest of the family. To them, living in a housing project was almost unimaginable. Our relatives either turned up their noses at us or pitied us. We were the lowest rung of the family. I was ashamed of my address, 2333 South Bambrey Terrace, of wearing the same clothes until they wore out, of our lack of money, and of every other characteristic of being poor.

Our new neighbors were hardly welcoming. I still remember the first few days of kindergarten when Irish and Italian kids would say to me, “You killed our Christ,” or the one that always stumped me, “You’re a devil with horns.” Somehow I became a deformed six-year-old murderer. For a while I’d subconsciously touch the top of my head, waiting for the horns to gr

ow, and I wondered, How could I possibly comb my hair with horns?

The only support system I had were my parents, whom I adored and who adored me. They followed the Jewish tradition, knowing that their central obligation as parents was to love their children and to tell them they’re the greatest people in the world. They did that well. I knew I was loved and I knew I was smart. I also knew that I could face the world armed with those two gifts. After all, what else did I have? They gave me the strength to persevere.

My father taught me to be quietly modest, although I occasionally (note: always) broke that rule. I knew my father had been in the war, that he had a Purple Heart, and that his plane had been shot down over the Pacific. That’s all I knew until he died and I went through his papers. He was a war hero who would only say to us, “I have a fake knee, it’s platinum and it’s more expensive than gold. When I die, dig it out and cash it in.” Neither he nor my mother would talk much about those times or about their grandparents, my great-grandparents, who died in the Holocaust.

One time my mother went to my grade school to defend me because the teachers had demanded that I sing “Onward, Christian Soldiers.” In those days there was still prayer in public schools, and they had us sing Christian songs. I didn’t know why I didn’t want to sing that song, I just didn’t. My teachers couldn’t, or more appropriately were unable to, force me to utter a word. Hence, my mother’s first of many trips to the school. Of course, that made everyone in Edgar Allen Poe Elementary—students, teachers, and principals—hate my guts. The compromise on the hymn was that I was to stand and be silent while everyone else bellowed out that they were “marching off to war.” So I knew discrimination from a very young age—from my affluent extended family, from the people around me in school, and even from the poor people in the project where I lived, who had their own noneconomic reasons not to like me. My refusal to sing “Onward, Christian Soldiers” was my first political action, my first defiance of conformity and the status quo.

Kids growing up in Wilson Park knew to make friends only with other kids in the neighborhood, not the kids across the tracks. My friends included my neighbor Barbara Myers, the only girl who would communicate with me. She was a slim blonde with buckteeth, glasses, and an unfortunate early case of acne, which never seemed to go away. This made her a fellow outcast, so we had a mutual bond. Mrs. Myers didn’t take to the idea of her daughter having a Jew for a friend, but since I was the only one Barbara had, she tolerated me. Barbara eventually became my first sexual relation—well, I’m not sure that’s what you’d call it.

Sexuality to my generation arrived in the form of the Sears, Roebuck catalog. That book showcased almost any item that was necessary for the household, including clothing. Every boy waited for the new edition to arrive, and when it did, the first page he turned to was the one with women’s lingerie. Let’s get this straight: they weren’t drag queens in the making searching for an outfit, but normal prepubescent boys looking for their first sexual thrill, and they found it from the various models posing in bras and panties. That didn’t really work for me. Actually, the only reaction it stirred in me was to make commentary on color choices. I would think, Gee, she might look decent if that dress was another color. What really worked for me was the men’s fashion section. My eyes were glued to the men in underwear.

There was no name for it, at least none that I knew, but somehow it seemed wrong that I was looking at the men in the catalog. After all, men were supposed to be eyeing and sizing up women. I decided to try it. And thus, my first foray into heteronormativity began. Let’s call it an experiment.

Somehow, kids in the neighborhood saw Barbara and me as a couple. Puppy love, they thought. We were friends, and for me that friendship might be used to discover this mystery that I couldn’t quite solve.

Barbara’s parents had one of those above-ground pools in their backyard. It was made of thin aluminum and had a flimsy plastic liner that you hoped didn’t get punctured during the first swim. It was about four feet deep and six feet in diameter, and of course it was a calming sea blue. One afternoon while in the pool together, my hand started to feel its way around Barbara. I closed my eyes as my hand traveled down her body. Feeling the top half didn’t do a thing for me, so I continued in search of that thrill that had been so well advertised to be at the bottom half. As my hand reached the most important part, it spoke loudly to my brain: Something is missing here. With that, I did what any other kid would do: I investigated. I put my head underwater, opened my eyes, and watched as my hand slipped into the bottom of Barbara’s two-piece swimsuit. She didn’t stop me. When I actually saw my hand there, it scared me so much that my mouth opened in shock and I swallowed so much water I almost drowned—a watery death filled with screams of “Yek!”

To say my experiment was unsuccessful would be an understatement. The thrill that other boys experienced with the scantily clad women in the catalog was, for me, false advertising. Years later, Barbara and I both had a good laugh about our little test. It was her experiment as well and the end result was that she liked boys. Guess we both had the same feelings.

* * *

It seems that every time you turn on the news or watch a talk show you hear about someone who was brought up in a public housing project and became a gazillionaire. While I’m not a gazillionaire, I’m well off, and I’m now proud of my roots going back to the Wilson Park housing project, 2333 South Bambrey Terrace.

Almost every politician talks about lifting people out of poverty. As someone who has been there, I can tell you most of them just don’t get it. They’ve never experienced the daily grind of poverty. Their romanticized solution is nothing more than solving a numbers and jobs game. To those of us who have been there, poverty is a culture, one that envelops your entire being, from the constant hunger and degradation, to the fear, despair, and hopelessness that never go away. Even if you get out and get a good job, even if you become a gazillionaire, you still worry, even if irrationally, about being there again. Poverty never leaves you. We poor, those of us who have gotten out, strive every day never to be there again. I for sure never want to go back to Bambrey Terrace.

Our two-story brick row home was constructed as cheaply as the city could get away with. There was no basement. The kitchen was a dark cubbyhole with a slanted ceiling that supported the stairs to the second floor. A bulb swinging on a single cord from the ceiling was the only lighting. There was a closet where washcloths and other sundry items were stored just off the kitchen. When I was growing up, that closet gave me the creeps.

Our dining table and four chairs took up virtually the entire room. It was a typical Formica table with aluminum chairs that had cushioned backs and seats. Next to the dining area was our living room, which consisted of a couch and matching end tables, a chair, and a television atop a faded reddish-brown Oriental-style carpet. On the second floor were two bedrooms, my parents’ and the room I shared with my brother. The family all used the same bathroom. Each of the bedrooms had a closet without a door, which my parents covered with curtains. I worried at night about who might be behind those curtains. Every night I prepared myself for Dracula and Abraham Lincoln to come lumbering out. Everyone can appreciate Dracula, the scary Bela Lugosi, but old Honest Abe? As a boy, for some reason the likeness of Abraham Lincoln frightened me.

Children are children even if you’re poor. You still ask for the things you want, the things you see that other children have. To this day the moment of my life I feel most guilty about came after I asked my parents to buy me something they couldn’t afford. In our house when you wanted something you went to my father. One day, while asking Dad for something, I don’t even remember what, he exploded like I’d never seen before. He tried to explain to me why he couldn’t get it for me, and then he began to cry. I can’t remember what he actually said but I know what it was about. He was crying because he couldn’t do better for his kids and felt like a failure. He tried to make me understand the “why” as he talked and

cried, but it was way over my head. Finally, he told my mother he was going to take a walk. Ashamed of the pain I caused him, I also ran out of the house.

My mom was Edith Bunker from All in the Family—the Jewish version. Fragile, soft spoken, and wouldn’t say a word against anyone. She was the most delicate, loving, decent human being I’ve ever known on this earth, but when it came to Dad she could be strong-minded. She loved that man no matter what. She followed us both out of the house that day and found me sitting on a park bench. “Mark,” she leaned over and tried to explain, her words still resonating today, “Dad means well. It’s just hard for him to make ends meet. We have to help him. He’s a good man.” Then she put on her best smile and said, “Let’s take a walk and see what we can find.”

Getting out of the projects was a treat, especially with Mom holding my hand. Passing Vare Junior High School we headed to Point Breeze Avenue, which in the 1950s was lined with cheap mom-and-pop shops.

After several blocks of walking my mother took me to a variety store, or what was once called a five-and-dime. She looked around and found the engine and caboose of a red plastic train set. They were wrapped in a see-through cellophane bag and were cheap. She asked me if I’d like them, and I screamed with delight. Mom handed the bag to me, and I held on tight. It was my prized possession. We then began our walk back to the projects, taking the same route past the beat-up school, with its overgrown weeds and unkempt ball field. As we entered Wilson Park she asked if I liked my toy. I reached into the bag and my train was gone. I said nothing. Seeing my reaction, she took the bag and found the hole in the bottom through which my toy had fallen out. She just started to cry. Watching my mother cry after all that had occurred that day, I wanted to cry and yell as well, but instead I got sick to my stomach. I just stood there in silence, awash in guilt. I had lost the toy and made my Mom cry. She quickly pulled herself together and we went home. It was never spoken about again, but it still makes me emotional.

And Then I Danced

And Then I Danced