- Home

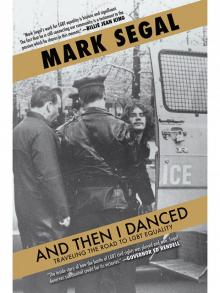

- Mark Segal

And Then I Danced Page 5

And Then I Danced Read online

Page 5

Yet activism was not glamorous. Revolutions are work-intensive and that kept me living on a can of SpaghettiOs and potato salad for dinner most nights. We only bought clothes, usually at thrift stores, when the ones we had were worn thin.

To support myself—barely, since we were creating a revolution and had little time to make money—I had a litany of jobs. The one that kept me going was, like my father, driving a cab. Dover was my garage, and even today I have my hack license hanging on my office wall. My other part-time job was as a waiter at John Britt’s Hippodrome, literally a rundown gay dive bar on Avenue A between 10th and 11th Streets. My most vivid memories of working there were from Monday nights when I got to be a bartender, since few people came in and John had no one else who would work just for tips. Only one customer stands out in my memory. Almost every Monday he’d sit at my bar, and often he was the only customer. We’d talk, but not about his business, which I’d learned many weeks into our relationship was dance and ballet. Robert Joffrey, of Joffrey Ballet fame, who was born Abdullah Jaffa Bey Khan to an Afghani father and Italian mother, never talked shop, thank goodness. In all honesty, the only thing about ballet that I actually like are the men in tights. It takes me back to those J.C. Penney catalogs.

As an organizer in the LGBT community, I was willing to drop any and everything just to be involved. This meant that I didn’t always show up for my shift at Dover to get my cab. New drivers like me sometimes demanded the better cabs that often went to the longtime drivers, and that didn’t sit well with the veterans. This led to a confrontation with three older drivers, all well built and intimidating, who cornered me one day and suggested that the garage didn’t need faggots making demands.

Since I couldn’t live on the money from the Hippodrome alone, some GLF friends suggested a solution: sign up for welfare. For a guy from a working-class family who had escaped the projects and envisioned never being a part of that world again, this seemed out of the question. But when the rent was due and the landlord threatened eviction, I realized my friends had a convincing case.

According to them, the state was giving us welfare as restitution for the despicable treatment gays suffered. Since it was society that was oppressing us as citizens, why shouldn’t we use their tools to fight back? When I researched how to sign up, it surprised me to learn that all one had to do in 1970 was walk in a welfare office and tell them you were “homosexual” and, because of that, you could not keep a job and therefore needed public assistance.

In desperate straits I made the journey and filled out the paperwork. As I waited for my turn to meet with the social worker, I wondered how hard the qualifying questioning would be and expected to be tossed out on my butt. When I finally got my turn, a bland man in a brown suit looked over my paperwork and muttered, “Homosexual.” He stamped the paper and said, “You’ll have to do counseling,” and directed me to another window to finalize my acceptance. That was it, with no further questions. As I got out of my seat, my anger rose. What it all meant was that the state of New York classified homosexuality as a mental illness and we, as a group, were incapable of working.

Was I using the system or was I validating their belief system? Regardless, it angered me. We were both wrong—and this act was somehow further impetus for me to help bring about change.

Back on Christopher Street, welfare somehow gave me cred with my fellow Gay Liberation Front members, which made it a little easier to swallow.

My life now had a purpose: in a very short span of time I had gone from quiet high school student to gay revolutionary with a minor in theater on the side. Meanwhile, my parents still thought I was in school. And I was—at a place called GLF University.

It seemed there was a demonstration almost every week. Leafleting was constant as we grew GLF. There was no Internet, no cell phones—just feet. We handed out papers on the street as people made their way to a club or restaurant or we pasted them onto poles and buildings along Christopher, Greenwich, Seventh Avenue, and other areas of the Village.

Then came a call from my father.

Chapter 3

Mom, Don’t Worry, I’ll Be Arrested Today

In 1971, hearing my father’s voice on the other end when picking up the phone was unusual. Calls from home always, always started with Mom’s greeting. So I knew this was no ordinary call. My father never made demands, he requested, and allowed one’s good sense to respond. This meant that he just gave me the facts: Mom had advanced kidney disease and needed a transplant, and an extra hand around the house might be useful at this time. Dad made the point that he wasn’t asking me to stop anything I was involved with. Most fathers, after finding out their son was spending his days fighting for LGBT equality, would have taken those words back, but not my father; he rejoiced in them. In many ways my parents soon became activists themselves.

After a visit to the library to research my mom’s illness, it struck me hard that what she had was tough to beat. Transplants in 1971 were 50/50 odds at best. The thought of losing Mom frightened me more than anything else that had been tossed my way.

Living, truly living, only began for me in 1969 when New York beckoned. Now I was returning, back to the place where I thought there would be nothing for me. I had a vibrant life in New York; Gay Liberation Front had become my family. We were brothers and sisters, and being one of the youngest in the group, I was often treated like a son. These were the people who brought about my understanding of why I’d felt as I did all my life. Now I had to leave; yet with my GLF University education under my belt, the tools of revolution were in my hands and in my heart.

Then it hit me: I’d been part of the movement and helped to create the Gay Youth organization in New York, so why not do the same in Philadelphia? In retrospect the timing might have been ideal, because soon after my departure from New York, the GLF organization imploded—but not before it gave birth to the next stage in community growing.

* * *

After selling his United cab 441, Dad had become a door-to-door salesman. He sold everything from encyclopedias to education courses to Jesus. Literally. His final big job was selling 3-D pictures of Jesus Christ in cheap plastic frames. Watching this short Jewish man hawking this tacky picture to a housewife was amazing. He started off by quoting a passage from the Bible, then he’d talk about Our Lord and the importance of having Him in not only our hearts but also our homes. If the pitch wasn’t going well he’d drop to his knee and say, “Let’s pray,” and begin reciting the Lord’s Prayer. That was often a closer.

After Dad decided it was getting too hard to do the door-to-door thing he began a new business buying and selling leather belts. These were slightly defective belts called “seconds” with a nick or some other minor flaw. He started selling them at flea markets for a dollar. He offered to bring me into the business, and though it seemed strange—after all, I was supposedly in an RCA technical repair program—what else could I do? Besides, the belt business was profitable. He was bringing in decent money from working just two days a week.

Times should have been good. But Mom wasn’t. Dad never accepted that she was as sick as she was. The only change in their lives now was that there was no more bickering about money that they didn’t have. Instead, Dad treated Mom like she was a queen, whereas in the past she had only been treated as a princess. Whatever Mom wanted, she got, but she rarely wanted anything—she would never take advantage of any situation or anyone.

Mom was a trouper, like her own mom. She never complained. When her condition deteriorated and she finally had to go on dialysis, her only complaint was that she’d have to quit her job. She was a floor manager at the E.J. Korvette store in Cedarbrook Mall, an early version of Kmart.

So my new life consisted of working with Dad and taking Mom to dialysis. She was often cheerful on the way to her treatment, but when I’d pick her up she was always exhausted and cold. One day while taking her to the hospital during a snowstorm, the car got stuck on a patch of ice. In a panic, knowing s

he needed her treatment, I jumped out of the car and flagged the first person who passed by, demanding they assist me in pushing the car out of its rut. For my mom I’d give the world.

In the evenings I began attending the local chapter of Gay Activist Alliance, which proved to be a little tame for me. The one exception was that after the general meeting, run strictly by Robert’s Rules, with a parliamentarian to boot, there was always a topic for discussion. Many quite interesting. At one of the first meetings I attended, a Dr. Dennis Rubini, who became one of the first in the country to teach LGBT history, at Temple University, was giving a talk on the food supplements he ate to create a more healthy body and save the environment. When a questioner asked him how he could survive with just the supplements, Dennis exploded and yelled about the genocide of cows to feed a capitalist society, and summed it all up with, “Anyone who eats meat, fish, fowl, or processed food is a pig.” Thereby trashing nearly the entire audience. Ah, I had now found my people. I was home again.

The Gay Activist Alliance’s major objective was to get a nondiscrimination bill introduced into the city council. At the time I joined, they were still unable to find a sponsor for the bill from any of the seventeen members on the council. My entrance from New York’s Gay Liberation Front gave me great credibility, and though it was arrogant of me to think that I would create a movement in Philadelphia where there already was one, and one that had been the vanguard for the nation in the past, I would try. What I wanted to do was redefine what that movement should look like and what it should achieve.

Not long after joining I was voted in as the political chair. My platform was built on the promise that, if elected, I’d get the bill introduced. This would be a complete change in my life, going from revolutionary to an elected chairman working with the city council.

I started to meet with city council members, even if they didn’t want to meet with me. Standing outside their offices, sitting on the steps of their favorite restaurants, or hanging out at the city Democratic headquarters was par for the course. They’d see me and sigh and I’d say, always with a smile, “You’ll break down one day and talk to me.” As time went on I’d start to joke with them: “Will this be my lucky day?” “Hey, I’m really a nice guy.”

Finally they began to smile and chat with me, first on the street, then having actual meetings in their offices. This was a big deal in those days. Politicians did not meet with “homosexuals.” The City Hall press began to notice me as well and started to run news items on my work. Zack Stalberg, the future editor of the Philadelphia Daily News, saw something in me that I hadn’t noticed as yet—dogged determination—as did show-biz gossip columnists Larry Fields and Stu Bykofsky. Somehow, what I was doing was fodder for good copy at the Daily News which, after all, was a tabloid newspaper. In an attempt to be more cutting edge than its sister publications the Philadelphia Inquirer and the Evening Bulletin, they hyped it up a bit. Those were the days of a big city having at least three daily newspapers.

As more and more people would talk to me, my profile began to grow. Producing a daily column is not an easy job, especially if it’s local gossip where you need to keep readers interested. So Larry Fields took almost anything I pitched to him, and as luck would have it, appearing in his celebrity news column miraculously made one a “celebrity.” It’s basically the same path to fame that Paris Hilton and the Kardashians used, minus the sex. Despite these superficial methods, celebrityhood opened doors. Those media mentions led to a radio talk show appearance to discuss nondiscrimination, which in turn led to a feature article and then to a TV interview. The cycle was then repeated. I soon had my city council sponsors and the bill was about to be introduced.

This first victory plowed the way for me on all other legislative and government successes to come. Our nondiscrimination legislation now had a number, Bill 1275. To become a law in the city it first needed to be read at a city council session. During council, most of the time, the clerk would read the bill number and title, which in our case was “a bill to amend the Philadelphia Fair Practice Ordinance,” and just move on. The audience in the chamber would have no idea what each piece of legislation really entailed. On the designated morning I went with my friend Harry Langhorne, president of Gay Activists Alliance, and sat in with the audience to watch the council. They were saluting the Boys Club of America for who knows what good deed this time and the North Philadelphia Catholic High School, which had just won a debate championship. The gallery was full of people from the various local Boys Club chapters and from archdioceses—students, a priest, and some nuns. Harry and I went around telling them that a bill was about to be introduced that supported Cesar Chavez and the California migrant lettuce pickers. We were going to stand and applaud when it was introduced and we would appreciate if they’d join us in the celebration. As we took our seats, Bill 1275 was introduced. Harry stood up and applauded on cue, then I stood and applauded. Like clockwork the remainder of the gallery stood up and applauded, and then everyone on the council joined in on the excitement. The following day, the headline in the Philadelphia Daily News was “Gay Rights Bill Introduced, Priest and Nuns Applaud.”

All lightheartedness aside, these early successes were meaningful. The bill got introduced, but we couldn’t move it out of committee since George X. Schwartz, the city council president, was a major homophobe. This led me to take various actions against the council. One of the most memorable, and one that brought me a lasting friendship, was a simple act of disruption. During a council meeting, we climbed over the railing separating the council chambers from the gallery and began to take over the chambers. Schwartz ran out as I approached. I sat in his chair, which was on a perch above the council, almost like a throne. Trying to do my best George X. Schwartz imitation, I plucked a cigar out of my pocket and stuck it in my mouth as I put my feet up on his desk. I took his gavel and brought order to the room. Just when I was about to do a pretend vote on Bill 1275, the sergeant-at-arms was called in along with the police. The sergeant, a very tall and big man, wrapped his arms around me in a bear hug and picked me up. While carrying me out of the chambers he gave me a friendly lecture. Rather than have me arrested, he deposited me outside the chamber in the middle of a group of visiting nuns. “The Wizard of Oz,” he said, and walked away laughing. That sergeant-at-arms is now Congressman Bob Brady, the ranking member of the US House Committee on Administration and Philadelphia Democratic City Committee chairman. A close friend of Vice President Joe Biden, he’s sometimes called the “Mayor of Capitol Hill.” His grace and good humor at that encounter led to a lasting friendship, a shopping partner in his wife Debbie, and a gay ally who knows the political ropes. He was the first politico to try and teach me “how to get business done.”

It was now December and the council was winding down for the year. If the bill didn’t pass by the end of the session we’d have to start the entire process over again. People were all abuzz with their gift shopping and holiday planning. In the middle of City Hall there was a Christmas tree, decorated in ribbon and ornamentation with a star on top. I decided to chain myself to it and announced that I’d go on a hunger strike until the city gave a hearing on the gay rights legislation. The press loved it, especially when I was asked why I was chained to the Christmas tree. “I’m the Christmas fairy,” I replied.

That headline didn’t move George Schwartz, but it did, surprisingly, move one Mayor Frank Rizzo, who sent an aide out to the courtyard to ask if I’d meet with him in his office. The reality was that I had no exit strategy on this action, so hell yes. It was another strange but lucky day in my life, one in which an invitation came from a mayor who’d once called San Francisco “the land of fruits and nuts”!

Later I heard from Marty Weinberg, Rizzo’s chief adviser, that when he said he wanted to meet me, his staff had cautioned against it. He overruled them and said, “I like the kid, he has balls.” The meeting went well and Rizzo explained that although he couldn’t tell the council what to do, he

could request that the Human Relations Commission hold the hearings. I left Rizzo’s office with a victory and with the knowledge that I would not have to spend the night chained to the city’s Christmas tree. Truth is, the reason behind his generosity was that Rizzo was in a feud with Schwartz. They were simply using me as a pawn. Though in reality, we were all using each other. We got two days of hearings out of it that led to two days of media coverage. We also got the final report issued by the Human Relations Commission, which stated, “There is obviously overwhelming discrimination aimed at members of the gay and lesbian community, and we urge council to pass legislation.”

This embarrassed Council President George Schwartz (later to be indicted in the infamous Abscam case that cited bribery, extortion, and conspiracy, fictionalized in the film American Hustle) so much that he decided to declare where he stood on the issue. He’d hold his own hearing in the council that he would personally chair. We finally got the hearings we wanted, but it was Council President Schwartz’s “big top.” Schwartz called in all the anti-LGBT troops he could influence to speak out against the legislation, including Philadelphia Cardinal John Krol regaled in all his clerical drag—purple robe, cape, rings, and shoes. All he needed was a tiara.

But Schwartz saved his best for me. As I read my prepared statement, every so often I would look up to gauge the reaction. At the councilman’s table, Schwartz looked like a caged lion ready to pounce. The second my statement was completed, when the chair usually asks if any of the other members of the council have any questions, Schwartz said, “I have some questions for you.”

In my head I said, Let the circus begin. And it did.

In front of a gallery full of spectators and a complete press pool, Schwartz started out by explaining that he didn’t understand people like me. Who are you people? What do we expect from people like him? What is a homosexual? Then he finally looked directly at me and loudly asked, “Mr. Segal, what do you do it with?” The look on my face and the silence in the chambers made him grow angrier and even more despicable. “I mean,” he shouted, “what do you do it with?” I could only stare at him, and in a rage he yelled, “Do you do it with parakeets?”

And Then I Danced

And Then I Danced