- Home

- Mark Segal

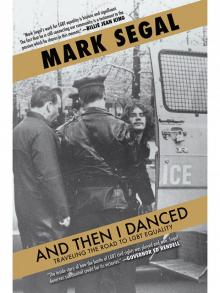

And Then I Danced Page 7

And Then I Danced Read online

Page 7

Larry has written about this in his autobiography, and his version seems to be a little embellished. He writes of blood on the walls. The only fluid that I recall being exchanged was the sportscaster’s makeup smearing my jacket as I yelled at him, “Hey, watch it, your makeup is getting on my shirt!” We were pushed to the ground and wrapped in cables until the police arrived and treated us to another nickel ride. This time I had friends to knock against. We got released without bail somehow, and we went to our respective homes to sleep. It was nearing four a.m.

The entire front page of the next day’s Daily News was devoted to the zap, and the story was picked up by almost every other news media outlet. The phone never stopped ringing. By the end of the day it was obvious that we had perfected the solution to invisibility. Action News had its format, now the Gay Raiders had ours. We were a force that could not be controlled. We had a laser beam on the networks. We’d hit them, and we’d hit them hard. No live or even taped show was immune to us, and we started reinventing ways to get into the studios.

First up was a syndicated variety show, The Mike Douglas Show, one of those mindless afternoon entertainment programs. I chained myself to the camera while crooner Tony Bennett and the first lady of the American stage, Helen Hayes, were getting their feet read by a professional foot reader. I started to do gay chants like, “Two, four, six, eight, gay is just as good as straight,” and almost anything else I could think of until they stopped taping. They brought the police in and before they could cut the handcuff I told them that until we had some form of agreement, I’d keep coming back. They agreed to have a gay spokesperson on the show, but not me. We settled on Reverend Troy Perry of Metropolitan Community Church, the man I had picketed against in my Gay Liberation Front days. His appearance was the first time an afternoon audience in America heard from a gay member of the clergy. Troy is an artful speaker and he made me and many others who saw that nationally syndicated show proud.

* * *

Next up was the Today show. To familiarize ourselves with the studio we took several tours offered by NBC. They were quite educational. We gained entrance to 30 Rockefeller Center in the early-morning hours and just waited in a closet. While the news was being read live I appeared on camera walking across the studio. I believe the director thought this was somehow part of the show. The news anchor actually got up out of his chair and, as some people described it, looked like he was trying to climb the walls. My first thought was to comfort the guy, but I was there for a reason and had to stay on mission. In midsentence I’m tackled and again wrapped in camera cables, then taken out to the hall with a security guard. As we’re walking away, me expecting to head off to jail once again, it was a relief to know that Morty Manford of the New York GAA was ready to bail us all out. Before anything else could happen, a woman yelled at the guard and told him to stop. Barbara Walters, the doyen of the morning news network crowd, with pen and pad in hand, walked over and asked me why we were protesting the show. My explanation was that it wasn’t just the Today show but all of network TV that censors us on their news, stereotypes us on their entertainment shows, and keeps us invisible by not having LGBT people on their programs. In the middle of this exchange a producer came out and told her to get back in the studio since she was about to go on air. She firmly replied that this was a story and she wasn’t going back in until she had it.

Years later, in January 2012, the Today show celebrated its sixtieth anniversary. To honor the occasion, Running Press published Stephen Battaglio’s From Yesterday to TODAY: Six Decades of America’s Favorite Morning Show. The book goes through the highlights of the sixty years and I’m proud that the zap was included. NBC, to secure my participation in the book, gave me a DVD of my zap, and it was the first time I got to see it in over forty years. But there is another connection with the Today show that few know.

I had many friends in the media. Edie Huggins, who had various programs on WCAU through the years, was one of the first African American women to host her own talk show. She called me to explain that the station wanted to do a pilot with a new staff member in order to determine if he had what it took to host a show. Would I do the station a favor and shoot a pilot with him? Then she added, “He is very pleasing to the eye.” His name was Matt Lauer. When I met Edie at the station, she explained that the show would be done in two sections. One with me “playing” the angry gay radical, then the second, me being my pragmatic self. They wanted to test Matt Lauer on how he would handle each scenario. He was only given my name and position as a gay activist. I arrived on the set; we were introduced, shook hands, and began the taping.

Matt opened the show then introduced his guest, me, and asked his first question. To my amazement he had done some research and asked me about the slow progress of nondiscrimination legislation. I wanted to get into real dialogue, but with my assignment in mind I replied, “It hasn’t moved because the legislative pigs in Harrisburg want to keep gay people in their place.” He kept going without a bat of his eyelashes: calm, cool, and polite; it almost made me angry. After ten minutes of this he segued into a fake commercial break. Then we began part two of the pilot. This time he asked a question about AIDS and how the mayor was handling it. While the question surprised me, since I was not used to local reporters doing proper research, my shift in demeanor surprised him. It’s a pleasure to meet a reporter who understands the issues and can appreciate all the areas that AIDS encompasses. Again we went on until another fake commercial, and then it was over. As soon as we heard we were done, everyone including Matt broke down in laughter. The pilot was picked up. Matt, you owe me.

* * *

Next up in my war against the media was what I thought would be the mother lode, Los Angeles. By this point the campaign against the networks was getting major press coverage as we zapped the networks from coast to coast. Along the way, Variety, the show-business bible, had an article on how the Gay Raiders had cost the networks over $750,000 in tape delays and lost revenue, a figure that in today’s dollars totals over three million.

Johnny Carson, king of late-night TV, was our next target. We expected this zap would be our largest audience to date and make the networks cave. This time we entered as audience members. During Carson’s monologue, which I knew they did in one take and couldn’t cut away from, I left my seat and walked to the camera and did my old handcuffs trick. Carson, the true pro, just kept up his monologue as his staff came over trying to cover my mouth. They gagged me and told me if I agreed to be quiet they would meet with us and try to negotiate a settlement. I nodded my head in agreement since I couldn’t speak. At commercial they cut me loose and then there were police in the studio. They had no intention of negotiating anything. A producer simply said that to get me out of there.

When the police deposited me and my partner on the Carson zap, Mike Walters (a volunteer for the LA Gay Community Services Center), at the Burbank jail after our zap of the Tonight Show, we were fingerprinted, photographed, and put in a holding cell. There were six cells that opened to a communal area where there was a table and chairs. There were only four other prisoners in the cell when we arrived and after all the official paper shuffling was done, we joined them. At first the conversation was basic. Where are you from, how old are you? The other prisoners seemed to be friendly and not dangerous—this was Burbank after all. It was all going well until one of the guys asked two men who looked like brothers why they were in the jail. The taller of the two said, “We killed a faggot. I hate those faggots.” They then asked me why we were there. Not giving them a second glance I headed back to my cell and closed the door, and remained there until my old friend Troy Perry of Metropolitan Community Church bailed me out. I sometimes wonder if the Burbank police staged that, and what would have happened if those two men knew the real reason we were in that jail with them. The Tonight Show did a good job of editing me out and they refused to meet with us, but Variety published an article on March 14, 1973, titled “A Segal Lock or How Taping Can T

urn into Gay Time for Carson.” As the story reported, “He then ran down the aisle to the rail that separates the audience from the stage and handcuffed himself. Guards followed and, when they told him to unlock the cuffs, were told he didn’t have the key. Segal was quoted as saying he had mailed it to Philadelphia.”

During this campaign against the networks in Los Angeles, it seemed that every hour was accounted for. Morris Knight and Troy Perry kept me entertained with parties and events almost every night. My living quarters most nights were in the Gay Community Services Center, then on Wilshire Boulevard, or on someone’s couch. One evening Troy took me along to a recently opened Jewish temple where they were to dedicate their new Torah. On another Morris visited a campaign cocktail party for a homophobic candidate for city council, telling me en route that the woman had no idea she was about to enter a party of gay men. He then told me he was giving me the honor of confronting the candidate. I’m not quite sure what I said but the next issue of the Advocate headlined the event as, “Candidate Flees Gay Party.”

On yet another occasion Morris took me to a fundraiser in the Hollywood Hills at the home of Terence O’Brien. Terry was the chairperson of the board of the Gay Community Services Center and had gotten his parents’ permission to hold a fundraiser in their home. As I walked around the tastefully decorated place, several items caught my eye. The first was sitting on the fireplace mantle. Slowly approaching the statuette and looking at it closely to see if it was indeed what it seemed, I picked it up. Within an instant Terry appeared out of nowhere, took hold of the statuette, and said, “My father doesn’t let anyone touch the Oscar, it belonged to a very close friend of his.” As I glanced to the corner of the room I could see Morris smiling. I walked over to him and asked who Terry’s father was. Morris looked coyly at me. “Pat, of course.” He was talking about the actor Pat O’Brien, who it seemed always played a priest or mob character. This brought a big smile to my face since it immediately made me remember him from one of my favorite old movies, Some Like It Hot.

Feeling a little foolish and not knowing Hollywood protocol, I just sat down to ponder the wonders of Los Angeles. Again Terry scolded me, this time saying, “Nobody is allowed to sit in that chair.” Abraham Lincoln, my childhood scare, had used it when he was a statesman in Illinois. I was completely out of my cultural league, but I took it as another lesson and an opportunity to observe a different group of people.

My LA adventures even saw me at one of movie star Rock Hudson’s “boy parties” where I felt even more out of place than in a TV studio. There were all these guys in skimpy bathing suits. All seemed to have great chests, short hair, many blond, and all were overly handsome. Hudson, himself exceptionally good looking, had a drink in his hand and seemed to be enjoying the view. Somehow the sight of me wearing old jeans and a T-shirt and my long hair down to my shoulders didn’t seem to please him, so we made a fast exit.

The following week I had passes to almost every show at ABC, which became our prime target and would be used as an example. We called Av Westin, the vice president of program development, and requested a meeting before the passes were to be used. Troy and Morris had identified a group of media experts to join us. That was the first meeting between a national network and the LGBT community. While Westin agreed to change entertainment policy, he was honest in explaining that the news divisions of the networks operated separately and he could not assist with our negotiations with them.

NBC and CBS quickly agreed to change programming in their entertainment divisions to be more sensitive to stereotypes and said they would consider adding LGBT characters. The campaign against the networks was almost a success, but we still had to tackle the news departments in New York. It was time to return to the East Coast. Troy Perry had to buy my ticket since I didn’t have a dime.

Once home, the brainstorming began. What could we do that would make the news divisions do what the entertainment divisions had done? We decided to follow the same formula and knew what had to happen. And that’s the way it was.

Chapter 4

Walter

Walter Cronkite, the most trusted man in America, and his CBS viewership of over sixty million people, would be the target that would fundamentally change the LGBT community’s national invisibility, though that never occurred to me at the time. To me it was just another zap, just another visit to jail, and just another long line of interviews about the zap. It was almost like I was going off to work, minus the salary.

It all started thanks to comedian Redd Foxx and his show Sanford and Son. Our campaign against the networks had already produced a lot of disruptions. We had gained a national reputation for putting broadcast media on notice. Either meet with us to discuss our grievances or suffer the consequences, the zaps.

Sanford and Son was about to get me on the zap trail again. They broadcast a show in which, for some strange reason, Redd Foxx’s son had to pretend to be gay. In order to do this he used every stereotype known to mankind. Swish, limp wrist, high-pitched voice, over-the-top and colorful clothing, the works. We caught wind of this and tried to meet with network executives before the airing, but the network felt they were covered by the agreements we made in Los Angeles. Their explanation was that the script had already been in preparation and it would be the last one.

Once the show aired, several activists from around the country urged me to take action since the media had been my area of expertise. GLAAD, the nation’s leading LGBT media advocacy organization, would not be founded until 1985, eleven years later. Until then, as disorganized as we were, there were only the Gay Raiders. There was also a feeling that the agreement the networks had made was not being taken seriously. They were testing our resolve. We needed to show them that the airwaves were in the public trust and not a place to continue to oppress the LGBT community.

Morty Manford, then president of Gay Activist Alliance in New York, called and suggested that I do something in New York again, to get the giants of network television to take notice. He also promised that once I decided on what my zap would be, he’d take care of finding me a lawyer. Both Troy Perry and Morris Knight also chimed in and felt that my kind of action was necessary to make the networks know that we were serious in changing their attitudes toward us. Even Frank Kameny, the first LGBT activist to sue the government in order to keep his government job—not to mention the organizer of those Independence Hall demonstrations back in the mid-1960s—was urging me on and giving advice.

The decision was obvious to me: expose their vulnerability with a zap. I’d go back to that first news zap, only this time it would be on live national TV. This would be big, and Morty and his offer for bail and a lawyer were absolutely necessary because we had no funds and no support system and I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life behind bars. Harry Langhorne, a close friend from GAA and member of the Gay Raiders, became my rock-steady coconspirator in this endeavor. We were not able to gain access by a tour as we had in NBC—there was no audience, and this was a closed set in a closed building. What could we do?

For some time, my friend Tommi Avicolli Mecca had been president of the gay organization at Temple University, and he was kind enough to allow the Gay Raiders, without the university’s knowledge, to use part of their budget to print materials and cover other small expenses. Tommi was a Gay Raider who also sat in on planning meetings. In one gathering at the Temple Gay Student Alliance office, Tommi, Phillip, Harry, and I discussed how to gain entrance to that secure studio. As we were debating, a student dropped by and grabbed a book he had left in the office. “I’m off to RFT,” he said. What was RFT?

Tommi responded, “Radio, Film, Television.”

“They teach television production here?”

Tommi nodded, and then came my request: “Tommi, I don’t care how you do it, but get me a sheet of their stationary.”

I had it the next day. We drafted a letter to the producer of the CBS Evening News explaining that we were in the RFT program at Temple Universi

ty and we’d like to view a broadcast from the control room in order to see firsthand how professionals use the equipment that we were just beginning to learn how to operate. It actually worked. We received a letter suggesting a visit two weeks later, on December 11, 1973.

As we entered the control room to the CBS Evening News we were introduced to the staff. During that time it was Harry’s job to scout the lay of the land, and as I went out to the studio he was to create any diversion necessary to allow me to get on air. Before our arrival at CBS we had timed the show and knew approximately when the commercial breaks would occur. We believed that once the show was being broadcast, everyone would be so involved that they wouldn’t notice anything we did until it was too late. We also wanted to time the zap just as Walter was coming back from commercial so that if we were tuned out, CBS would have to explain to the viewers what had happened. No cutting to commercials and denying it.

The usual format for the CBS Evening News was to go live at six p.m. to about 60 percent of the nation. In those days there were no twenty-four-hour news channels. People got their TV news from one of three networks, and the CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite was the untouchable leader for eighteen years. The audience of millions of people who saw that show and their first openly gay person on national television would not be equaled until April 1997 when Ellen DeGeneres came out on her prime-time show on ABC. Will and Grace, considered the first network show with an out character, finally moved past those earlier milestones in 2000.

Their usual pattern called for CBS to later rebroadcast the six p.m. show to the remainder of the country or, if breaking news warranted, they would broadcast it live again. At about fourteen minutes into the program, as Walter Cronkite was reporting to the American public about security procedures for Henry Kissinger and Richard Nixon, I knew this was the moment, and for the first time while doing a zap my heart started beating very fast. I wasn’t scared but somehow I knew that after this event things would change forever. I rushed onto the set, holding up my sign and yelling the message printed on it, “Gays protest CBS prejudice!” The CBS Evening News broke down right in front of Walter. I stepped between him and the camera, thereby shutting him out of the picture to show only that sign. As millions watched, I sat on his desk and held the sign right into the camera lens so that everyone could clearly see the words. Gays Protest CBS Prejudice.

And Then I Danced

And Then I Danced