- Home

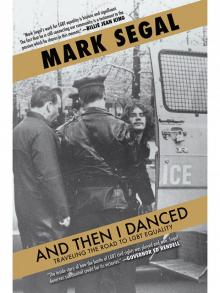

- Mark Segal

And Then I Danced Page 8

And Then I Danced Read online

Page 8

Noted historian Doug Brinkley’s best-selling 2012 biography and Washington Post “book of the year,” Cronkite, best captures the scene:

The days of lax security at CBS News abruptly ended on December 11, 1973, when twenty-three-year-old Mark Allan Segal, a demonstrator from an organization called the Gay Raiders, with accomplice Harry Langhorne at his side, interrupted a Cronkite broadcast, causing the screen to go black for a few seconds. Cronkite was delivering a story about Henry Kissinger in the Middle East when, about fourteen minutes into the first “feed,” Segal leapt in front of the camera carrying a yellow sign that read, “Gays Protest CBS Prejudice.” More than thirty million Americans were watching . . . “I sat on Cronkite’s desk directly in front of him and held up the sign,” Segal recalled. “The network went black while they took me out of the studio.”

On the surface, Cronkite was unfazed by the disruption. Technicians tackled Segal, wrapped him in cable wire, and ushered him out of camera view. Once back on live TV, Cronkite matter-of-factly described what had happened without an iota of irritation. “Well,” the anchorman said, “a rather interesting development in the studio here—a protest demonstration right in the middle of the CBS News studio.” He told viewers, “The young man identified as a member of something called Gay Raiders, an organization protesting alleged defamation of homosexuals on entertainment programs.”

Segal had a legitimate complaint. Television—both news and entertainment divisions—treated gay people as pariahs, lepers from Sodom and Gomorrah. It stereotyped them as suicidal nut jobs, flaming fairies, and psychopathic villains. Part of the Gay Raiders’ strategy was to bring public attention to the Big Three networks’ discrimination policies. What better way to garner publicity for the cause than waving a banner on the CBS Evening News? “So I did it,” Segal recalled. “The police were called, and I was taken to a holding tank.”

But both Segal and Langhorne were charged with second-degree criminal trespassing as a result of their disruption of the CBS Evening News. It turned out that Segal had previously raided the Tonight Show, the Today show, and the Mike Douglas Show. At Segal’s trial on April 23, 1974, Cronkite, who had accepted a subpoena, took his place on the witness stand. CBS lawyers objected each time Segal’s attorney asked the anchorman a question. When the court recessed to cue up a tape of Segal’s disruption of the Evening News, Segal felt a tap on his back—it was Cronkite, holding a fresh pad of yellow lined paper, ready to take notes with a sharp pencil.

“Why,” Cronkite asked the activist with genuine curiosity, “did you do that?”

“Your news program censors,” Segal pleaded. “If I can prove it, would you do something to change it?” Segal went on to rattle off three specific examples of CBS Evening News censorship, including a CBS report on the second rejection of a New York city council gay rights bill.

“Yes,” Cronkite said. “I wrote that story myself.”

“Well, why haven’t you reported on the other twenty-three cities that have passed gay rights bills?” Segal asked. “Why do you cover five thousand women walking down Fifth Avenue in New York City when they proclaim International Women’s Day on the network news, and you don’t cover fifty thousand gays and lesbians walking down that same avenue proclaiming Gay Pride Day? That’s censorship.”

Segal’s argument impressed Cronkite. The logic was difficult to deny. Why hadn’t CBS News covered the gay pride parade? Was it indeed being homophobic? Why had the network largely avoided coverage of the Stonewall riots of 1969? At the end of the trial, Segal was fined $450, deeming the penalty “the happiest check I ever wrote.” Not only did the activist receive considerable media attention, but Cronkite asked to meet privately with him to better understand how CBS might cover gay pride events. Cronkite, moreover, even went so far as to introduce Segal as a “constructive viewer” to top brass at CBS. It had a telling effect. “Walter Cronkite was my friend and mentor,” Segal recalled. “After that incident, CBS News agreed to look into the ‘possibility’ that they were censoring or had a bias in reporting news. Walter showed a map on the Evening News of the US and pointed out cities that had passed gay rights legislation. Network news was never the same after that.”

Before long, Cronkite ran gay rights segments on the CBS News broadcast with almost drumbeat regularity. “Part of the new morality of the ’60s and ’70s is a new attitude toward homosexuality,” he told millions of viewers. “The homosexual men and women have organized to fight for acceptance and respectability. They’ve succeeded in winning equal rights under the law in many communities. But in the nation’s biggest city, the fight goes on.”

Not only did Cronkite speak out about gay rights, but he also became a reliable friend to the LGBTQ community. To gays, he was the counterweight to Anita Bryant, a leading gay rights opponent in the 1970s: he was a heterosexual willing to grant homosexuals their liberties.

During the 1980s, Cronkite criticized the Reagan administration for its handling of the HIV/AIDS epidemic and later criticized President Clinton’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy regarding gays’ nondisclosure of status while in the military. When Cronkite did an eight-part TV documentary about his storied CBS career—Cronkite Remembers—he boasted about being a champion of LGBTQ issues. And he ended up hosting a huge AIDS benefit in Philadelphia organized by Segal, with singer Elton John as headliner.

Here’s what’s not in Brinkley’s book: Within moments a handful of technicians came over and wrestled me harshly to the floor and wrapped me in wires. They were angry and rough. It’s my belief they were acting out of loyalty to Cronkite. I was beaten and bruised. For a while I remained outside the studio with two guards while they decided what to do with me. I remember thinking in a daze about the stagehands and technicians. Were any of them gay? How did they feel about what I had just done? Did they hate me?

We were then ushered to an office on the first floor of the building under armed CBS guard, and told that we were not free to go. We were a little confused since at no point did they tell us that we were under arrest. Finally the door opened. In walked the anchor of the local CBS Evening News with a camera crew and several guys in suits. They told us that it would help to be interviewed. Who it would help or for what reason they didn’t say. Nor would they answer any of our questions. It didn’t matter. Our goal was to get the word out to the public and this was one way of doing so. We were proud to assist and would suffer any consequences later.

We were also not aware of how big a deal this all was. Later we discovered that the CBS switchboard was so overloaded that it was brought down, and many of those calls came from other media, so the network knew it had a story and they also had an exclusive story that they could keep for their own broadcast. After the interview, security guards led us down a hall, at the end of which stood a group of New York’s finest. A police wagon had been brought to a back door and CBS did all it could to shelter us from being photographed while going from the door to the police wagon. We were their exclusive. When we got to the doors, escorted by the men in suits and the armed guards, all hell broke lose. Every news organization in New York was there. As the CBS guards handed us over to the NYPD, reporters kept yelling questions and flashing pictures.

While we were being transported off to jail, Walter Cronkite was doing his second live news broadcast of the evening. He reported on the disruption of his earlier show “by a group calling itself Gay Raiders and protesting CBS bigotry toward the homosexual community.” In commenting on the zap during his own show, Walter was not aware that it was the first time the CBS Evening News had ever reported on a gay demonstration.

The next morning the story was on the front page of nearly every newspaper in the country. America wanted to know more about this man who dared hurt their Uncle Walter. It was beyond my comprehension. Requests for interviews started to come in as soon as we were out on bail. A couple of publishers asked me to write a book about my zaps, another wanted a memoir. A memoir? At twenty-three? Others fe

lt they could somehow market me, make me a celebrity du jour, but I had no interest in any of it. My purpose in all of this was gay equality.

As the face of the Gay Raiders, I was invited to more on-air talk shows. News magazines and newspapers called for interviews. At times I felt the country simply could not comprehend a gay man who was not only open, but outrageous, proud, pushy, and also happy and fabulously full of life and humor. Offers came and all I asked for was transportation, a hotel if necessary, and meals. This was not for money; even though I had none; I was still living off the grace of my parents. I became the penniless darling of the media, and the first openly gay person to make the talk show circuit. There were other prominent activists out there like Frank Kameny, Barbara Gittings, and Harry Hay, but none of them had captured national attention as I had by disrupting Walter Cronkite’s newscast. My intention was to sell gay liberation like a product, by educating the nation about LGBT people.

The hosts of the shows would introduce me as this radical controversial homosexual, and then I’d do my darndest to be a polite and gracious guest. If it was my plan to show America who gay people were, then I had to play the part, which, luckily, mirrored who I really was. Morty Manford, as promised, had arranged for a lawyer. Not just any lawyer, but Hal Weiner, who had been the attorney to incorporate the GAA. While I zapped people in person, Hal zapped them with the law. In my first meeting with Hal, he looked at me sternly and said with what felt like true annoyance: “Do you know you could get ten years in prison for this?” He waited until it sunk in, then started laughing and added, “You won’t get ten minutes.”

The morning after the zap, Hal called the CBS lawyers and asked to come in to subpoena Walter Cronkite. The CBS lawyer laughed and told Hal that Walter was too busy and then hung up. Hal did a little research and learned that at that time, New York law allowed a subpoena to be copied and then used as a legal subpoena. So he called the CBS lawyers back and said, “Before you hang up, I’d like to let you know about the subpoena powers here in New York.” After he explained the law, the CBS lawyer asked, “What the hell does that have to do with us?” Hal then said: “I’ve just made one hundred copies of the subpoena and tomorrow at eleven a.m. I’m coming in to CBS, and you will have Walter available for me to subpoena him in person. If not, I’m giving fifty subpoenas to members of the Gay Activists Alliance and fifty to Hell’s Angels, and I will offer a thousand-dollar reward to the first to serve Walter.” Needless to say, Walter was served the next morning at eleven a.m.

While preparing for the trial, the Gay Raiders even appeared in a Life magazine feature called “A Day in the Life of America.” Nothing like a couple of gays not making a living.

Most gay people at the time were still not supportive of our efforts. Many believed that we should be quiet, conformist, and stay in the closet. Some were ashamed of me and tried to suppress our work. As the nation’s best-known out gay man I was doing national television shows with rips in my socks and holes in my shoes. Harry Langhorne, who stood lookout during the Cronkite zap, had to ask his mother for financial help. A distant relative of Lady Astor finally paid our out-of-pocket legal expenses when Morty, Morris, Troy, and even Frank Kameny, who was having his own problems making a living, were unable to get financial assistance for the defense.

I’ve kept a few of the notes I received at that time to remind me of where we were. One states: While we admire your intentions, we do not admire your methods. Another, from a wealthy friend who loaned me $150, which I thought he understood would be paid back whenever I had the funds, said, I’ve never run into such a dishonest person before. But there were those of support as well: a group of lesbian feminists from Miami sent what they could, and we did receive small donations but not enough to either live on or pay legal bills.

Today, activism is a multimillion-dollar business, with huge budgets and all kinds of wealthy backers. At that time, not one major celebrity or corporation embraced our community, much less the radical Gay Raiders.

At our trial most reporters were surprised to see Cronkite listed as a defense witness. A tape of the zap played, and Walter witnessed his open jaw during the incident. Hal asked him his reaction and Cronkite said, “Not very professional on my part,” which gave everyone in the court a laugh.

As for Walter and me, we became friends. As Brinkley wrote in his book and made public for the first time, Cronkite kept his promise, but all the while he never admitted that CBS News was biased on the subject. Not while introducing me to key CBS News staffers—including Marlene Adler, his chief of staff who over the years kept us connected—not after reporting on those cities that had passed gay rights legislation, not when reporting on gay pride. It actually became a running joke between us.

Chapter 5

After Cronkite

Sixty million homes. That’s how many people saw the broadcast. There was a burning-bright spotlight on the LGBT community and on me personally. The public just wanted answers. Some wanted me strung up for hurting good old Uncle Walter, and many members of my own community thought I had gone too far. But we had succeeded in our attempt to capture the public interest and we were ready to start a discussion. Percentage-wise, Walter’s newscast was a juggernaut; his ratings then were higher than most shows on prime-time television today.

When Harry Langhorne and I had been released on bail and left the police station, only Morty and Hal Weiner, our attorney, were there to greet us. We talked strategy with them, then drove back to Philly. It was my turn to take Mom to dialysis that afternoon. At home she was waiting at the door. She gave me a hug and asked if I was treated okay. It had all become so normal for us. Mom would ask about the police treatment, about the cell, and about next steps. It was like any other mother asking her son, How was your day at the office? She was the caring mother to the hilt, no matter how sick she got. I assured her I was all right, then she insisted on cooking breakfast for Phillip, Harry, and me. The phone was ringing off the hook but we ignored it for as long as possible. Once we started to answer, it was call after call of requests for interviews for newspapers, magazines, and radio and television talk shows.

The next two years I was fully engaged with appearances on talk shows, other interviews, and making speeches across the country. I’d fly out to Chicago to do a television show, then to Los Angeles for a speech after the taping, and then do a radio show while waiting in the hotel to leave for my flight to yet another city. We still did the occasional zap, but getting publicity every six weeks via a stunt was no longer necessary; publicity was following me.

At the time, the king of the television talk shows was Phil Donahue. His syndicated show was first taped in Dayton, Ohio, before moving to Chicago and then New York. It’s ironic to say that he was the Oprah Winfrey of his day, since many give him credit for inventing the genre and ultimately it was Oprah who dethroned him as talk show champion.

Somewhere along the way, I was invited onto the Phil Donohue Show. Before the show he came into the makeup room to explain to me that his audience was conservative. This didn’t bother me because I’d known that he had done one other program on the subject of “homosexuals,” during which he was sympathetic and respectful. While his other “homosexual” guest had tried to win the audience over with simple facts, my attitude would be very different. Per my Gay Liberation Front training, respect was demanded. This conservative audience was about to be challenged by a gay man, and one who would tell them that all they had learned about the LGBT community was wrong. My reply to Donahue was, “Do you think they’re ready for me?” He seemed to enjoy that.

Like most talk shows, after the guests on Donahue were introduced, the host would begin with an introductory question or two. The real meat of his show, however, was the audience’s questions, where Donahue would run up and down the aisles with his microphone.

For my first question, Donahue wanted to understand why we’d done the various zaps on network television. The answer in this case was simple. “Phil, would

I be here today discussing this issue if we hadn’t done those zaps?” It was true. “Thanks to those zaps, more televison and radio talk shows are now debating this subject, and so those acts far exceeded any expectations we had.”

When that softball question was over he went to a lady in the audience who held up a Bible and wanted to quote from it. Donahue persuaded her not to open the Bible but invited her to say what was on her mind. She looked at me and told me I was going to hell and that God intended for me to die. “Says Leviticus,” she bellowed, “Man who lays with man is an abomination!” She was just going on and on until Phil interrupted her and asked if she’d like to hear my response.

“Madam, from what you say it seems you don’t respect religion,” was my reply.

She said, “I’m a true Christian.”

I stared her down. “A true Christian respects the rights of other religions. My religion accepts who I am. Are you inferring that Judaism is a false religion? If you’d like to talk religion we can do so, but I’ll also quote other parts of the Bible you seem to have forgotten.”

She exploded and just started tossing out various biblical verses at me.

And Then I Danced

And Then I Danced